Unlike as it may seem, the title of this exhibition is far from being a statement or just an observation. It is actually a question, or a riddle, that was present throughout the inception and production processes of what is now displayed at Galeria Athena’s Cube Room. It starts from the idea that seeing the landscape cannot be just noticing what is around us – it should rather be thinking about the very matter of which our surroundings are made. It highlights the difference between to see and to look. To see is to question, to see twice. To look is not to be satisfied with a passive position and to turn our eyes (and our entire body) more active. A simple landscape is not ordinary at all.

Therefore, the works by Castagneto, Volpi and Pancetti present in this exhibition remind us that our history (not only the history of Art, but history in general) has landscape as a milestone of its beginning and later restart. The narrative of the “discover” of Brazil goes through the idea of an exotic, non-European, landscape as recorded by the former artistic and scientific expeditions which – in addition to fauna and flora – also depicted ‘human types’. The oldest work present in the exhibition is a small painting by Castagneto, dating back to the late 19th Century. To current eyes, it might seem a conventional painting, but it is rather a reflection of the artist’s participation in the so-called ‘Grimm Group’. German artist Georg Grimm was a professor of Landscape, Flowers and Animals at the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts (Aiba) – created in 1826 and which pioneered the study of Arts in Brazil inspired by the European Art Academies. In 1884, Grimm resigns due to disagreements with the Academy’s leadership and other professors over their teaching methods. No longer an Academy member, he establishes an open-air studio at the Boa Viagem beach, in the city of Niterói, where he stimulates plein-air painting alongside other artists, including some former Aiba students, such as Antonio Parreiras and Castagneto himself. This change strongly influenced Grimms’s painting, who set academic (European) principles aside, like precision, realism and proportion, in favor of free brush strokes, strong action painting, and a tendency to monochromatism.

Decades later, in the prime of the Republic in Brazil, the façades by Alfredo Volpi and the José Pancetti’s marine paintings, for instance, are echoes of a dissatisfaction that had already been noticed in previous initiatives, such as the Grimm Group, which strived for avoiding the outside view in the construction of our imagery (and our history). The 1922 Modern Art Week is a milestone of that discussion; it advocated the need for rediscovering Brazil. Seeing our landscape and our history with “free eyes”, as stated by Oswald de Andrade in the ‘Pau-Brasil’ Manifesto, permeates part of the artistic output of the first half of the 20th Century, and finds an echo in the search for autonomy that characterizes modern art. Regarding the works of Volpi and Pancetti, the contemplation of landscape is the starting point to structure the form simplification process towards abstraction, and a reference for the geometric works that would become a trend in the 1950’s in Brazil.

In addition to painting, As far as the eye can see includes photographs, objects, sculptures, interventions, collages, videos and audios, unveiling the possibility of contemporary interpretations of landscape that go beyond a more historic dimension. The exhibition includes works from the past five decades, some of which have not been displayed before, and depicts the “landscape” as a subjective, inconstant, moving element. Landscape is no longer a backdrop, a setting where something happens, but the foreground, taking the leading role. It is also the eyes of the artist and those of a less passive audience. Wanda Pimentel refers to the historic landscape painting and makes the form of a window and the form of a canvas coincide. Here, we “see” one of the most famous views of Rio de Janeiro, as well as the window frame. Works by Debora Bolsoni [Banglã is a structure that resembles a large window, or a stage, the fabrics of which respond to movements and flows of air in the space where it is displayed], Julia Arbex [the Sedimentação / Sedimentation are the result of the time the artist keeps the paper in contact with water and clay], Thiago Rocha Pitta [turning landscape moves visible, which oftentimes are invisible to the naked eye, such as eclipses and meteorite falls] and Vanderlei Lopes [freezing a moment in time and a landscape moment evidenced by the displacement of light] differently point out to the time that passes at a speed that is not our speed (the reason why we hardly ever notice it).

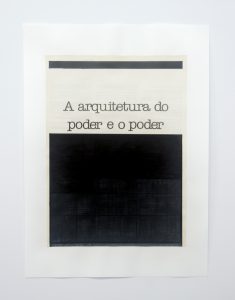

There are also works that see the landscape as a territory – a space resulting from the action of humans, by highlighting its dimension and political meaning. Ideas such as borders [Antonio Dias, Frederico Fillipi, Lais Myrrha], instability [Ernesto Neto], displacement [Floriano Romano, Lara Ovídio, Matheus Rocha Pitta], design [Andre Komatsu] and scale [Ana Dias Batista and Debora Bolsoni] stress the concept of landscape as a construction – which leads us to think that, as it is constructed, it is so by someone with a certain motivation in a particular time. In this set of nearly 40 works from 17 artists, Até onde a vista alcança / As far as the eye can see utilizes an apparently comfortable and harmless starting point, like the landscape, to present dialogues between different artists and stimulate the audience’s eyes to appreciate art and its surroundings.

Fernanda Lopes

More: Galeria Athena